It is a completely normal day in the lab. It is just past eight o'clock, and PhD student Asbjørn Cortnum Jørgensen is ready in his white coat. Everything has been prepared. He has set up his petri dishes, a liquid full of nutrients and dissection equipment. Now he is just waiting for his pig’s eyes.

The eyes are coming from Danish Crown. As soon as the pigs have been slaughtered, the eyes are put on ice and driven at express speed to Aarhus University.

Asbjørn is a little impatient. As soon as the pig is killed, the eyes begin to decompose. Asbjørn must therefore get hold of the eyes as quickly as possible after slaughter. Otherwise, the cells will be dead.

His eyes finally arrive and he can begin his experiments.

Asbjørn puts the eyes in a petri dish filled with nutrient-containing fluid that can keep the cells alive a little longer. He keeps the dish at a constant 37 degrees, like inside the pig's body.

Now he can relax. In the warm liquid, the cells in the eyes can survive significantly longer. Many days His goal during his PhD is to make them survive for a whole week.

With his eyes secured, he can begin his experiment.

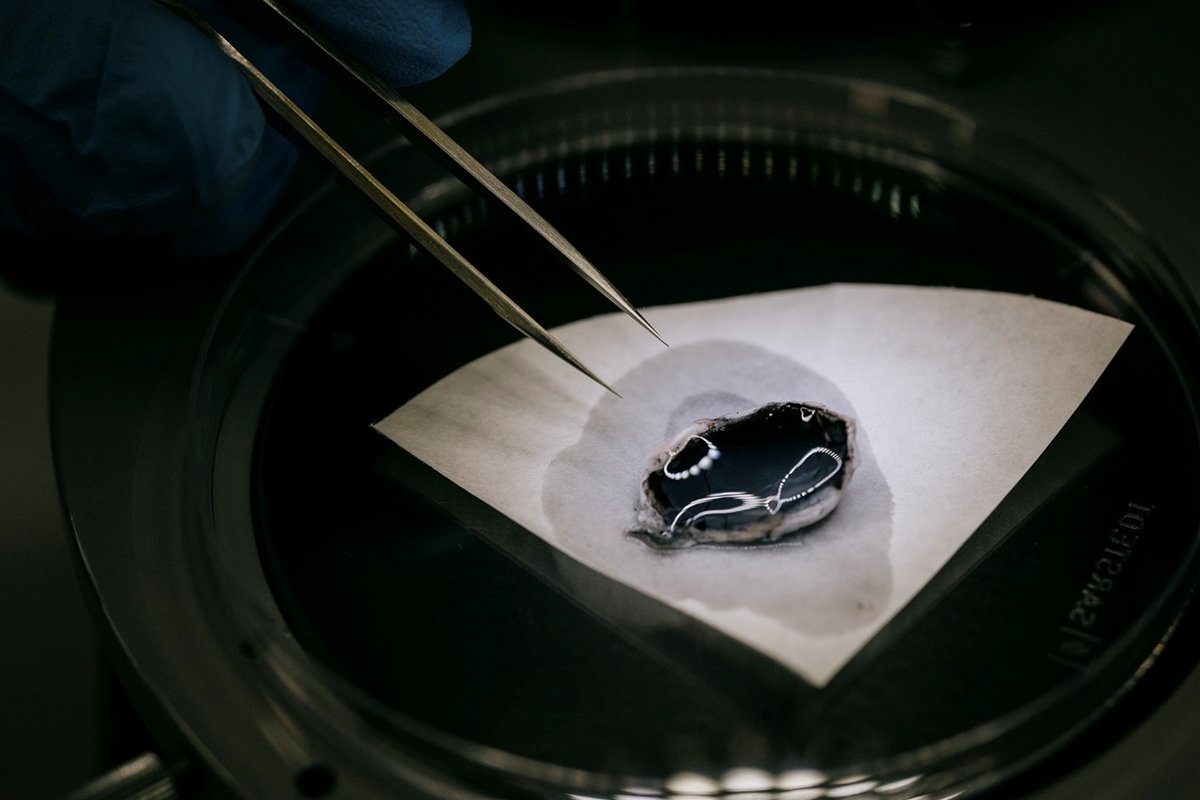

What Asbjørn is trying to do is implant tiny solar cells in the back of the pig's eyes and get the solar cells to emit electrical impulses when light hits them.

The idea is that the solar cells will take over the task after the photoreceptor cells stop functioning in patients with the disease Retinitis pigmentosa.

In a healthy eye, light hits the photoreceptors, which then emit an electrical signal that is picked up by the neurons just in front. The electrical signals travel through the brain and to the visual centres, which translate them into the images of the world we see.

Researchers elsewhere in the world have succeeded in inserting a similar implant in patients. The patients even got some of their sight back, Asbjørn explains.

“It was far from their full sight, but from nothing they could see rough silhouettes and differences in the strength of light. So the implants work, but not perfectly,” he says and continues:

“In my project, I’m trying a two-pronged treatment. By supplementing the implant with a gene therapy, I hope I can improve the results.”

In the world of bacteria, there is a group of proteins called opsins. These proteins are photosensitive, and uniquely, they can detect light through a very simple process. The process does not require multiple steps, as is otherwise the case with other light-sensitive mechanisms in bacteria.

Opsins are the key to the second part of the two-pronged treatment that Asbjørn hopes to develop during his PhD

By grabbing the DNA sequence in the bacteria that enables them to make opsins, and then inserting it into the neurons at the back of the eye, Asbjørn hopes that they will be able to take over from the photoreceptors.

“It’s still at a very early experimental stage, but I hope that, by giving the cells in the neuroretina the gene that codes for opsin, we can enable them to capture light,” he says and continues:

“In people with Retinitis pigmentosa the rod-shaped cells that pick up the light die little by little, and the patient eventually becomes completely blind. But if the remaining neurons take over the photoreceptors' ability to capture light, we may be able to restore some of the sight.”

What's new about Asbjørn's PhD is combining the implanted solar cells with a gene therapy that delivers a new gene into the cells, enabling them to absorb light again.

Although Asbjørn has only been working on his PhD for a few months, he has known for a long time that this was what he wanted to do.

“Research has always appealed to me, and a PhD is a great opportunity to delve deeply into a topic. I don't know if I want to continue at the university as a researcher, but now at least I’m getting to try it out,” he says.

Going where no one has been before and mapping new territory motivates Asbjørn.

And it’s great that you have so much responsibility for your own project.

“You’re responsible for running the project yourself, and if you run into a problem, you have to reach out to others to solve it. I like that. You develop completely new sides of yourself.”

If everything in Asbjørn’s PhD project succeeds, it may really make a difference for patients suffering from Retinitis pigmentosa. And his project is far from the only meaningful project in which you can make a difference in the world.

“I also applied for another project, but chose this because it was the most exciting. There are lots of exciting projects out there. If you’re passionate about it, then just apply,” he says and continues:

“And don't worry if you don't have top marks. The most important thing is that you’re passionate about your project. Then the academic side will follow.”

Asbjørn will spend the next three years on his PhD, and he has not regretted it once, even though the pay is better in the private sector.

“Perhaps I'll stay at the university. Perhaps I'll end up in something completely different. Right now, I’m doing what I want to do. For me, it’s important to listen to myself and to what is most meaningful for me,” he concludes.

25 years old

Born and raised in Germany with two Danish parents. First lived in Neuss close to Cologne and Düsseldorf, but the family moved to Kobbermølle near Flensburg in 2008 so that the children could attend a Danish school.

After upper secondary school, he decided to study in Denmark at Aarhus University, from where he holds a Master's degree in molecular medicine.

Applied for a PhD position at the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering because he was attracted by the interdisciplinary perspective. However, he has had to learn more programming and a lot about solar cells, which was not part of his basic education.

Asbjørn's PhD project is supported by the AUFF NOVA programme from the Aarhus University Research Foundation. A scholarship is given to "bold and innovative research projects".

Asbjørn is employed at the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, with Assistant Professor Rasmus Schmidt Davidsen as his principal supervisor. The project is being carried out in close collaboration with Professor Thomas Corydon from the Department of Biomedicine, where the pig eye experiments are being carried out.